Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Networks (DEPINs) have successfully freed ordinary people to participate in the disruption of large, entrenched industries dominated by centralized, monopolistic entities. We’re seeing DEPIN entrants like Helium Attack Telecom and Hivemapper go after Google and Apple Maps. Each of these decentralized networks allows for the paving of infrastructure that would cost billions of dollars to build were it not for the labor and capital of the contributors to these networks, who are rewarded with digital currencies for their contributions. These networks collect data about the real world or provide a service whose value will only grow as more people and devices contribute to those networks.

One of the lesser-known and capital-intensive datasets to collect is real-world sound and audio events. You’re probably wondering, what kind of sounds are worth tracking in the real world, and how hard can they be?

The answer to this is very valuable and very difficult!

Let’s expand on one example of sound occurring in the real world, which is very valuable in tracking and capturing its existence and how a few oligopolies have dominated this world for centuries.

The sound we are referring to is music, and the location of this sound is in public places where commerce takes place, such as bars, restaurants, concert venues, nail salons, shopping malls, gyms, cafes, etc.

A little background on copyright first! In most countries, there is a legal right known as copyright. Copyright is a legal protection for original works of authorship that gives creators exclusive rights over their creative works. It protects the expression of ideas in various forms, such as:

-

Literary works (novels, poems, articles)

-

Musical compositions

-

Films and audio-visual works

-

Works of art (paintings, photographs, sculptures)

-

Computer software

-

Architectural designs

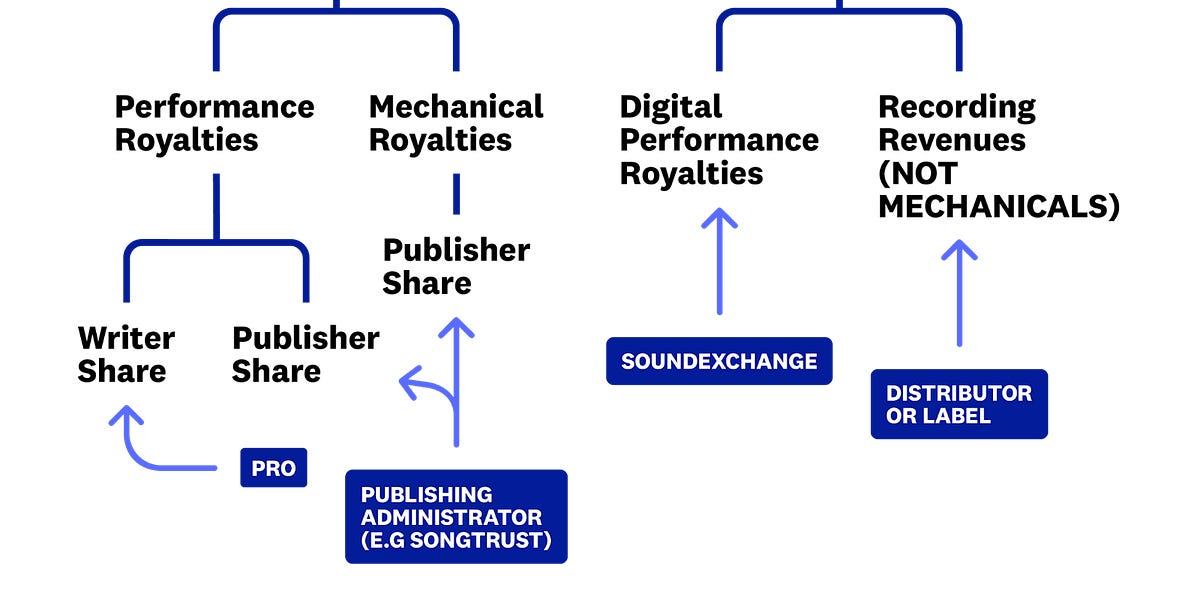

Owners of these copyrights can receive royalties from others for the right to use or benefit from their copyright. For music, there is a copyright inherent in a recorded composition or song. One copyright is the recording, i.e. the actual sound recording, while the other is the synthetic copyright, also known as publishing (the underlying music and lyrics). You may think that musicians, publishers, labels, and artists can only collect two types of royalties from these copyrights, but in fact, up to six types of copyrights can be created from these copyrights.

-

Mechanical royalties: These are earned when music is reproduced physically or digitally, including streaming and physical copies such as CDs or vinyl.

-

Performance royalties: These are generated when copyrighted music is performed or played publicly, such as at bars, venues, concerts, radio, television, or streaming platforms in public places.

-

Sync royalties: Paid when music is synchronized with visual media, such as in movies, TV shows, commercials, or video games.

-

Music printing rights: Obtained when copyrighted sheet music is copied, printed and sold.

-

Digital performance royalties: Paid to recording artists when their songs are played on non-interactive digital streaming platforms, such as Pandora.

-

Recording fees: These are generated from the actual audio recording, and are often collected by recording companies.

Below is a picture of how the royalties are divided:

The equity we will focus on that has the greatest potential to transform due to DEPIN is performance equity. Performance royalties are earned when a piece of music (a piece of music) is played or performed in a public place, whether it is performed live in a music venue, in a bar or café, or on the radio. (Note that streams from on-demand streaming services, such as Spotify or Apple Music, in public spaces earn performance and mechanical royalties—this is unique among types of music use.) Music owners—songwriters or their publishers—collect performance royalties.

All performance royalties are collected and distributed by collecting societies known as performing rights organizations (PROs), and sometimes called collective management organizations (CMOs). Professionals are entitled to performance royalties when songs in their repertoire are performed publicly. In most countries there is only one PRO who acts as a bridge to collect and distribute these royalties. Often, these national public research institutions are non-profit organizations and have a monopoly on collecting performance royalties in their countries. USA is unique in that it has three primary professionals who collect the vast majority of performance revenue. Until very recently, these three organizations were non-profit organizations. Now, SESAC is owned by Blackstone, New Mountain Capital recently acquired BMI in 2022, and only ASCAP maintains its nonprofit status.

Collectively, these three organizations raise more than $6 billion in revenue, with a 6-10% cut for their services. Globally, professionals collect approximately US$13 billion in performance revenue in their countries. Each of these PROs has reciprocity with other PROs to collect on behalf of the repertoire each PRO represents. However, 42 countries worldwide still do not have PRO.

Venues must pay a performance fee if they have live performances at their venue. Live performances can be actual bands, music over speakers, DJs, or even music coming from televisions inside the venue. Most venues pay a blanket licensing fee/royalty to each pro in order to utilize their repertoire. This blanket license fee is calculated based on the occupancy of the venue, the frequency of live performances, and a range of other attributes, such as whether dancing is permitted in the venue. Professionals have no way to verify this information and mainly rely on places that follow the honor system (spoiler: most of them don’t).

As these blanket royalties are collected, PROs must distribute them to the relevant rights holders based on repeat performances at venues. The truth is that professionals have no idea what songs are being played in places. Thus, the professionals distribute these royalties based on which songs are the most popular songs played on the radio as they can track that. This clearly creates a disconnect and leaves some rights holders overcompensated while others are undercompensated.

With this background, one has to wonder how these professionals collect and distribute these royalties, and better yet, find out which venues offer live performances.

The answer is that it is very difficult to know which venues are performing live and keep track of which songs are actually played live at these venues.

This problem is magnified because many venues themselves do not know that they have a legal obligation to pay royalties to PROs for performing songs in the PRO repertoire. Additionally, most venues have very little incentive to self-report since screening professionals have no effective way to detect and prove that screenings exist in the first place.

I can attest to this personally. I was running seven bars and restaurants and didn’t know I needed to pay for them. A team visited two of my pubs in 2017, and that was how the idea for Uvo was born. There have been no visits since then, and no visits during the 30 years my family ran said restaurants before 2017. Checking for copyright infringement once every 30 to 40 years is not a great way to ensure compliance. They do this because they are either not motivated to become more aggressive or they believe they will have a negative ROI due to having to pay field teams of employees.

Professionals globally spend hundreds of millions of dollars on field teams within cities to track live performances in unlicensed venues or enlist offshore BPO operations to contact venue owners and convince them to obtain a blanket license based on information gathered by smuggling public websites and social media. These methods are expensive, ineffective, and lack the real evidence that PR representatives need to prove they happened in court.

It is estimated that performance professionals collect only 3-5% of the performance royalties owed globally because performance professionals have no effective way to identify public performances and the data associated with those performances.

Enter the UVO network.

The UVO Network aims to democratize voice data through a decentralized, people-run network. Leveraging the 7 billion smartphones in circulation, UVO turns these devices into “super sensors” and data collection nodes. This data populates the Decentralized Sound Map (DSMap). Smartphone contributors earn tokens for contributing this data.

One of the first applications built on the OVO network is UVO+, a decentralized application (dapp). UVO+ is a community platform focused on addressing the growing gap between currently tracked public performances and what is performed in the real world, and the project encourages users to contribute hyper-local live performance data by offering rewards in the form of UVO network tokens.

Using an innovative tokenology model, UVO+ aims to create a sustainable and engaging ecosystem where users actively define live performances while leveraging their contributions in the form of tokens and real-time performance insights in their cities. By collecting accurate, real-time data, UVO+ seeks to identify every location where public performances take place and ultimately track public performances in real-time to accurately allocate performance royalties to rights holders.

With over 7 billion smartphones in circulation, these devices contain some of the most advanced sensors known to humanity. These sensors can not only record the music being played in real time, but also where and when that performance takes place. Tokens can further incentivize a contributor to tag, annotate, and leverage live performance data to create robust evidence of infringement and accurate data to determine a true blanket license fee.

Professionals would have to spend billions of dollars to hire global teams to track all the live performances and data needed to calculate accurate licensing fees. Professionals have an incomplete list of places and have no idea what is actually done inside these places.

DEPIN makes this happen at a scale and with an efficiency impossible by centralized PROs. Furthermore, the ubiquity of contributors in any city provides a strong incentive for venue owners not to drop their license fees because the network never stops.

This widespread coverage and real-time tracking of every live performance will eventually motivate these venues to install fixed sensors within their venues to track live performances 24/7. In this scenario, the venue now also earns tokens and only pays for what is actually played. It’s a win-win for the venue, the UVO Network and the rights holder.

The UVO datasets will train a live music detection and classification model, making on-site sensors 100% accurate. Existing music detection and classification models such as Shazam perform poorly at identifying live performances and cover songs because there is not a large set of annotated live music data to train them.

UVO will have the world’s most comprehensive live music dataset, which can be used to power professional masters and achieve almost 100% global coverage of live performances. This PRO will be compensated any time a song is performed publicly around the world. Performance rights royalties will rise to become one of the largest categories of royalties.

The UVO Network will have an open API where enterprise Web2 and Web3 platforms can purchase live performance data to improve their applications. Imagine looking at Yelp and seeing what songs are being played, either on speakers or by a band, at restaurants in your scene list, or opening Snapchat and seeing where live shows are happening in your city and what songs are being played real-time.

UVO data will also prove valuable to investors looking for data on mispriced performance returns that have been underestimated due to PRO’s current method of allocating equity.